Roland Barthes is a French philosopher who was heavily influenced by the structuralist linguistics of Ferdinand de Saussure. Barthes begins his essay ‘Rhetoric of the image’ by pointing out that linguists don’t attribute the status of ‘language’ to all types of communication, using as an example the ‘language of bees’ or the ‘language of gesture’ because those kinds of communications do not work the same way that language by system of difference. He argues that while it is true that bees communicate, birds communicate and gestures are a way to communicate, they are not the same as language because language (according to linguists) works by virtue of an arbitrary relationship of the difference of the different signs. He then asks if images can they be analysed in the same way that language is analysed. Barthes cites two opposing views on this question; there are those who think that the image is an extremely rudimentary system in comparison with language, with the other side saying that images have an ‘ineffable richness’ that includes some signification, or some messages that mere language just cannot do justice to. Barthes writes that if the image is, in a way, the limit of meaning then it could be used to understand how signification works, it could help to answer questions about how does meaning get into the image and where does it end. For this essay, Barthes uses the structuralist concept of the signifier (the form of the image) and the signified (the concept or idea it represents) to analyze how images function as signs.

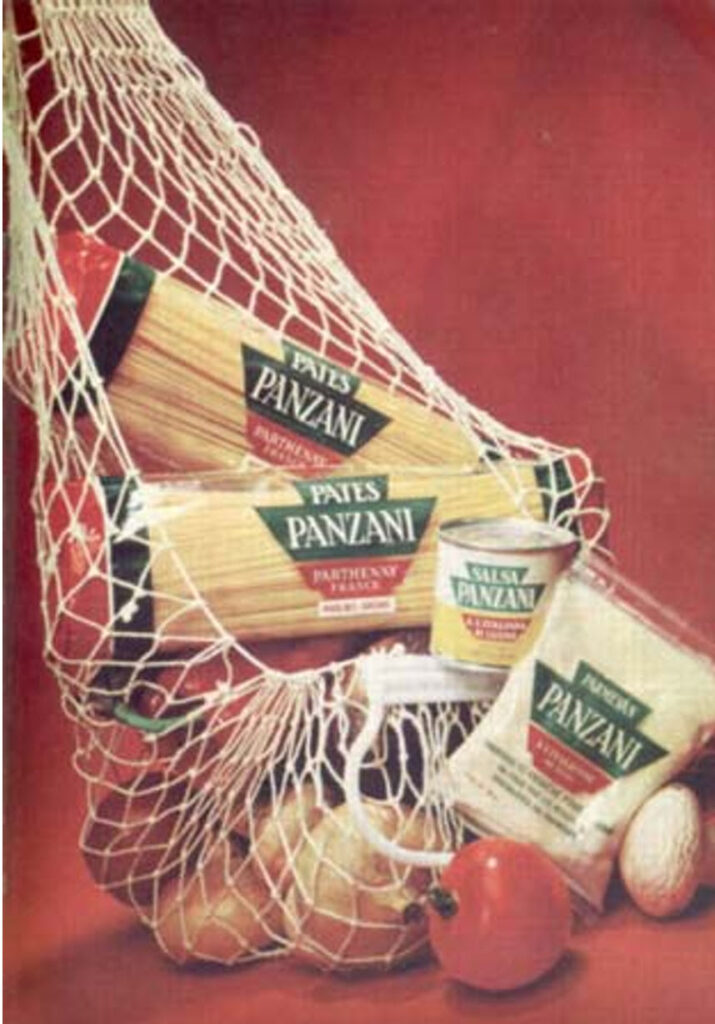

To do this, he uses an advertising image to explain this. The reason he uses the advertising image is because ‘the signification of the image is undoubtedly intentional; the signifieds of the advertising message are formed a priori by certain attributes of the product and these signifieds have to be transmitted as clearly as possible’ (Barthes, 1962,p 152). Meaning that when a business that sells the ingredients of pasta dinner creates an advert for its products, it intends for you to think positively about pasta dinners and to associate that particular brand with good pasta dinners.

He notes four different signs that can be found in the image:

- the first is the idea of someone returning from the market, giving the feeling of freshness produce and domestic preparation. This is achieved by depicting a net bag one with canned goods, plastic wrapped pasta along with fresh items (tomatoes, peppers, mushrooms, onions) tipping out of the bag as if it has been place on a kitchen table when arriving home.

- the second sign is the one produced by the colours of the tomato, pepper and the colours green, yellow and red reminding the viewer of the Italian flag. Yet again to remind the viewer of the image’s Italianicity. This is supported by the Italian sounding brand name ‘Panzani’.

- the third sign is the sense of a completely natural cooking experience. By combining natural products with the Panzani packaged products, it introduces the idea that Panzani products are as ‘natural’ as the tomatoes, peppers and onions.

- the fourth sign comes from the way the image is composed. It reminds the viewer of the countless still life painting of idyllic kitchen and food scenes

Barthes also points out that several of the signified objects in the image are iconic, so unlike the arbitrary connection between the signifier ‘dog’ and the four-legged canine, the relationship between a photo of a tomato and a real tomato is not arbitrary but analogical, so there is no need to make any connection. This is where Barthes believes the relationship between language, or a ‘true sign system’ and the image breaks down because unlike language which is a system of signs with a code, images present a message without a code. Consequently, in order to read this level of the image all that is needed is the knowledge of the objects. However, he also recalls that what the eye sees can be interpreted in many different ways depending on who the viewer is.

He concludes that the image presents us with three different messages; the linguistic message which we resolve according to the code by which we understand language, and two iconic codes, the first one (the denoted image) in which a picture of a tomato represents a tomato, and a second one which is the iconic cultural message (the symbolic message) that allows us to understand that the bag, its contents and its colours are to be understood as having Italianicity.

The linguistic message

Barthes points out that the first message the image displays is linguistic, referring to the caption of the image and the labels on the food products. The picture does not appear to have the caption but it would seem that that the caption that goes with the image is in French and basically says it’s pasta and sauces. It is Italian food products being advertised in French magazines. The linguistic message is twofold; it denotates food products and connotates a sense of ‘Italianicity’.

Barthes explains that the linguistic message can serve as an anchor for the image. Anchorage can guide or limit the interpretation of the image. It serves to direct the viewer’s attention, explain the intended message, or provide specific information about the image. This anchorage can also have the effect of reducing the range of interpretations a viewer may have of an image. It can do this by stating certain facts or ideas.

In addition to limiting interpretation, the linguistic message can also be used to expand on what is in the image, for example through context or background information.

Barthes points out that an image is not a standalone entity but is part of the bigger semiotic system. Consequently, the linguistic message also interacts with the image’s denotation (literal meaning) and connotation (symbolic associations) to construct the overall meaning of the image.

The denoted image

The denoted image refers to what is immediately visible. It is the most basic and straightforward interpretation and usually refers to objects, people, places, or scenes. When describing the denoted image the viewer would typically identifying objects, their shapes, sizes, colours, spatial relationships, without trying to interpret any addition meaning.

A denoted image can be understood by anyone from any background; for example, a photograph of an apple would denote the image of an actual apple, and this understanding would be mostly consistent across cultures.

For Barthes, the denoted image is the foundational layer of meaning in the semiotic system. Additional layers such as connotation are built on top of the denoted image. While the denoted image deals with the objective, concrete elements, connotation is concerned with how the image is interpreted by the viewer and therefore is influenced by culture.

The symbolic message

The “symbolic message” refers to the meaning of an image that goes beyond what is denotated and connotated. The symbolic message involves the understanding of the symbols in image that convey deeper meanings. Like the denoted and connoted parts of an image, the symbolic message is the key part of semiotic analysis because it is concerned with how signs and symbols convey meaning.

These meanings are not always obvious and often need a deeper level of interpretation because they represent things like values and beliefs. This is why symbols in images have cultural significance and are understood only within that specific cultural context. Different cultures may interpret the same symbol differently, and at the same time viewers will also add their won subjective interpretation based on their background.

The symbolic message adds complexity to an image’s interpretation. One image can contain multiple symbols, each with its own set of connotations and meanings. These symbols may interact with each other to create a layered and nuanced message.

Barthes “Rhetoric of the Image” explores the complexity of visual communication and the ways in which images convey meaning through various layers of interpretation and the interplay of signs and symbols.

Reference:

Barthes, R. (1964). Rhetoric of the Image. In Image – Music – Text, Stephen Heath. 1977. 32-51, Hill and Wang.